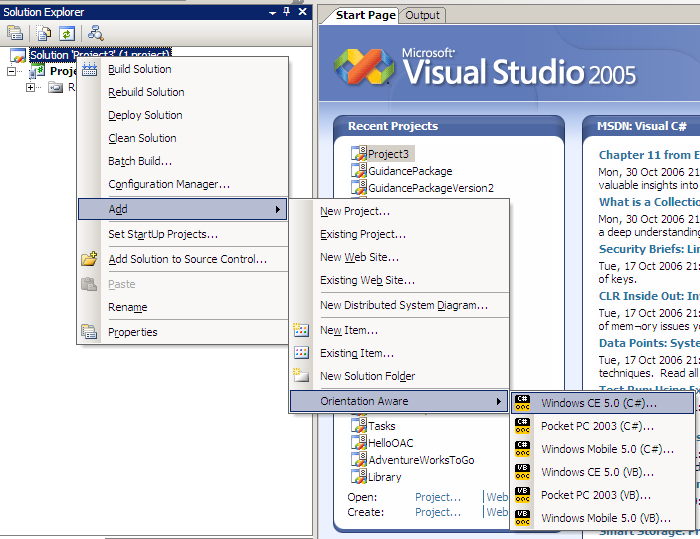

I’ve been thinking a lot about Visual Studio extensibility and its APIs evolution over the years. It’s amazing how fast these last 15+ years doing extensibility went by. The first product my company built shipped as a Visual Studio 2005 “Whidbey” extension (then, 2008 “Orcas”):

The fact that the product was both a Visual Studio extension and for mobile app development, created almost exactly 8 years before Xamarin bought the division is butterfly effect mind-boggling.

There were basically two main APIs to extend VS back then

- DTE: a.k.a. the automation model, originally (to the best of my knowledge) intended for simpler extensibility and macros, not entirely unlike the automation models for macros in Excel and Word back in the day.

- IVs*: the “real” extensibility API that you used if you were serious about extending VS and knew what you were doing.

Learning either wasn’t particularly easy, with very little documentation to speak of, so most of the learning was through practical exploration, trial and error and perhaps some IL disassembly (but not much initially since most of it wasn’t managed code).

On the role of documentation

It’s easy to attribute the steep learning curve to that lack of documentation. And it’s also easy to understand how big of a challenge it is for a quickly evolving IDE with many pluggable features developed by multiple teams to keep such docs up-to-date and consistent. Not to mention the API designs themselves consistent!

But if I learned anything after two decades of doing .NET in Visual Studio (and open source!), is that you seldom need docs when an API is intuitive, consistent and simple. Not to compare the miscule API surface of Moq with the VS APIs, but nobody has seriously complained about there never being an official API docs site for it in over a decade. I can’t even remember consulting the vast .NET/BCL API docs themselves to understand how to use them (for the most part).

On learning through exploration

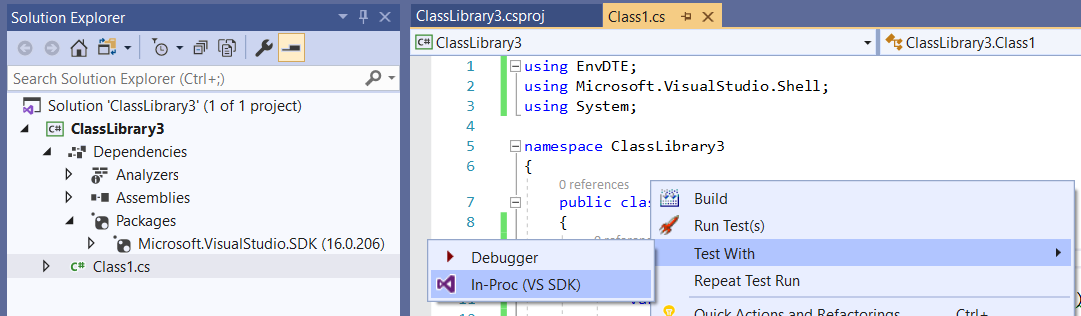

Back when I started extending Visual Studio, there was one indispensable tool I use to this day (first extension I always install, always): TestDriven.NET. One very little known feature of TD.NET is that it has an “ad-hoc” test runner (meaning it can run any parameterless method in any class) with one key twist: it can also run the code in-proc, in your actually running VS. This means that with just a regular class library and a single package reference, you can run code that exercises any VS API:

If I didn’t know (say) what DTE.Solution.FullName returned, I could just

write and run this code in no time:

public class Class1

{

public void DTETest()

{

var dte = (DTE)Package.GetGlobalService(typeof(DTE));

Console.WriteLine(dte.Solution.FullName);

}

}

I just learned that the great Jamie Cansdale has even added the ability to directly inject VS and MEF services as method parameters! So the following test passes, for example:

public void SolutionFullNameTest(DTE dte, IVsSolution solution)

{

var dteSln = dte.Solution.FullName;

ErrorHandler.ThrowOnFailure(

solution.GetProperty((int)__VSPROPID.VSPROPID_SolutionFileName, out var vsSln));

Debug.Assert(dteSln == (string)vsSln, "Hm, looks like they aren't the same?");

}

It’s obvious you could do this differently: “just” create an integration

test project (try finding the docs on using MSTest with [HostType("VS IDE")] ;)),

and run it (after patiently waiting for another VS to start on every run).

Clearly, the in-process quick run is immensely better for learning :).

I was recently reminded of the amazing learning power that comes with this live exploration approach when I played with GitHub’s new GraphQL API Explorer which is massively superior to traditional REST API discoverability, IMHO.

On API discoverability

Over the years, a third API “style” was introduced via MEF, initially mostly for the core editor extensibility rewrite in VS 2010 (no more fancy memorable codenames that I can recall from that point on ;)).

It seemed to be a big improvement over previous APIs, but in practice, the

learning curve didn’t improve much. The biggest issue was discoverability:

in order to know what you could do, you had to read the docs. There was no

way you could just simply “explore the API”. Much like IVs* where you

needed to know what service to get from an IServiceProvider among the

sea of types, in MEF you have to know what you can import and from what

context. Might even be worse in that respect :(.

In contrast, DTE was somewhat better: just “dot into” it and see what’s

there (i.e. dte.Solution.SolutionBuild.ActiveConfiguration). But you are

typically at least two or three dots away from what you want, and the API is

almost impossible to evolve nicely since now you need to cast the various

“dot” parts to newer interface versions to get the newer members (i.e. DTE

to DTE2, Solution to Solution2, Solution3 or Solution4, and so on) and

now it’s a mess. Consistency isn’t great either, even if it all sprawls

from a single entry point.

Parting thoughts on extensibility API design

I even took my own shot at improving

the situation with Clide (first version

going back 8 years already!), which was intended to be a DTE-like minimal

skeleton powered by MEF components, that could be infinitely extensible by

placing the right extension methods on the right “dots” in the IDevEnv

entry-point API. It was an improvement, but still not entirely satisfying.

In the Xamarin days (~2014+), we needed cross-extension communication but very loosely coupled (for versioning/evolution reasons, i.e. UI designers <-> core/project system communication), and another design became much more practical, based on the concept of simple DTO messages being passed around.

One thing became abundantly clear to me over this whole journey: you just can’t design an extensibility API like you would design any other regular library. I don’t think the principles you’d apply to a typical library (think Moq, xunit, HttpClient, AppInsights, System.Text.Json or any other) work that great in a highly heterogenous, dynamic and evolving space like extensibility. Yes, it’s possible the resulting design isn’t super obvious to a “typical library user”, but I’m quite sure anyone who’s done any serious Visual Studio extensibility can tell you there’s already very little of that in the current VS API models.

I think the IDE extensibility space is a fundamentally different domain that merits serious consideration of alternative paradigms moving forward.

/kzu dev↻d