Open source sustainability is a tricky topic. I would kindly refer you to the thoughtful post by Eric Sink and Six Labors’s license change post.

Suffice to say, we all struggle to make this a sustainable proposition where we can dedicate full-time to the projects we love. Also, there doesn’t seem to be a perfect answer for all scenarios, so there’s always pros and cons.

With that in mind, let me introduce you to SponsorLink.

GitHub Sponsors

GitHub Sponsors is a fantastic thing. I’m quite convinced it’s a step in the right direction, with availability throughout most of the world, and constantly adding new regions.

They have an Explorer to find projects to sponsor, and for the most part they have figured out how to make the quite tricky part of actually charging and paying people throughout the globe seem like a trivial thing. It’s quite amazing. No individual could ever have enough bandwidth to figure it all out on his own just to attempt to make a few bucks from a passion project.

I have been testing it out for a while too with an

organization account, but other than a few

generous friends and some one-time large-ish sponsorships (very few and far between),

let’s just say it hasn’t gotten much traction. Shocking, right?

As I’m getting ready for a serious amount of work on Moq vNext, I wanted to see if I could come up with something to help me support myself and my family while I dedicate to that full-time for a while. So I came up with SponsorLink.

Introducing SponsorLink

I believe most fellow developers don’t have an issue with giving away a buck or two a month for a project they enjoy using and delivers actual value. And I’m quite positive that if a couple dollars a month is an affordable proposition for an argentinean, it surely isn’t a crazy thing for pretty much anyone.

And I’m a firm believer that supporting your fellow developers is something best done personally. Having your company pay for software surely doesn’t feel quite as rewarding as paying from your own pocket, and it surely feels different for me too. We really don’t need to expense our employers for a couple bucks a month, right??

So the goal of SponsorLink is to connect in the most direct way possible your sponsorship with your library author’ sponsor account. And since the place where you spend most of the time enjoying your fellow developers’ open source projects is inside an IDE (i.e. Visual Studio or Rider), I figured that’s the first place where you should be reminded that either:

-

You are an awesome backer and the project is alive and well thanks to you:

-

You should not forget to take action now to become 1), given it’s incredible straightforward and affordable!

How it works

SponsorLink will never interfere with a CI/CLI build, neither a design-time build. These are important scenarios where you don’t want to be annoying your fellow oss users. I don’t want to have to deal with setting up licenses on a server, provisioning test agents or whatever. Also, if you’re building from the command line, it’s not as if you’re enjoying my oss library all that much anyway.

Initially, I built support for SponsorLink for .NET via a nuget package. The backend is agnostic to the client, though, so if this takes off, I may add other ecosystems.

The non-dotnet specific way it works for library users is:

- If the user isn’t using an editor or there is no network, there’s nothing to do, so bail quickly.

- A library author runs

git config --get user.emailduring build to get the current user’s configured email. If there’s nogitoremail, there’s nothing to do. No real work is done nowadays without both, right? :) - A quick HTTP HEAD operation is sent to Azure Blob storage to a relative URL

ending in

/apps/[user_email]. If it’s a 404, it means the user hasn’t installed the SponsorLink GitHub app. This app requests read access to the users’ email addresses, so the previous check can succeed. - If the previous check succeeds, a second HTTP HEAD operation is send to Azure Blob

storage to a URL ending in

/[sponsor_account]/[user_email]. If it’s a 404, it means the user isn’t sponsoring the given account.

In both 3) and 4), users are offered to fix the situation with a quick link to install the app, and then sponsor the account.

NOTE: the actual email is never sent. It’s hashed with SHA256, then Base62-encoded. The only moment SponsorLink actually gets your email address, is after you install the SponsorLink GitHub app and give it explicit permission to do so.

On the sponsor account side, the way it works at a high level is:

- One-time provision of your account, by installing the SponsorLink Admin GitHub app and setting up a Sponsors webhook in your dashboard to notify SponsorLink of changes from your sponsors.

- Integrating the SponsorLink for .NET nuget package and shipping it with your library: it ships as an analyzer of your library.

And that’s it!

From this point on, any new sponsor will immediately be notified to SponsorLink which will update the Azure Blob storage account with the right entries so that in mere seconds the experience quickly goes from Install GH app > Sponsor account > Thanks!

Closing

I discussed this approach with fellow developers and it sounded unanimously reasonable. Hopefully you will think so too, and perhaps even start using it on your projects. More than 20 years after my first steps in open source, for the first time I feel this can actually work and be a sustainable endeavor. Let’s make it work together!

Please do report issues and join the discussions. I want this thing to work and offer the best balance of gentle nudging users to sponsor (without being obnoxious) and being easy to integrate in your projects.

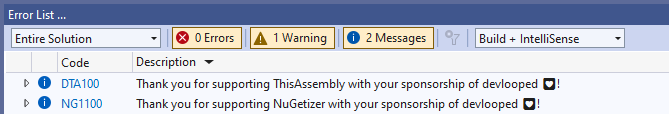

You can test the experience by installing any of the latest ThisAssembly packages or NuGetizer. If you are sponsoring Devlooped, you’d get a couple thank you 💟:

Now, it’s time for me to go back to doing what I like most: hacking on more oss stuff.

/kzu dev↻d