As I mentioned in my introduction post on SponsorLink, open source sustainability is a tricky topic. I have been doing open source for more than 20 years, so I’m not entirely n00b to the space. I don’t believe in “experts” anyway, so I’m just going off of my personal experience, things I read and saw other fellow developers do in the past and so on. So, if it wasn’t clear enough, I’m not speaking for anyone but myself. I don’t represent the “dotnet OSS community”, or speak as to “how OSS should be/is done” or what is “right” or “wrong” here.

The feedback I got was overwhelingly in the following areas:

Trust

Many were adamant that there was a serious violation of trust because I was doing something completely nefarious and evil, on purpose, and for some ulterior obviously bad reason.

The “obviously nefarious” part was me explaining 6 months ago that I was going to use one-way SHA256 hashes of your git email in a repo to try to easily map that to your GitHub sponsorship on the backend (static Azure blob storage). The actual plain-text email was not shared at all until you explicitly installed a GitHub app that requires explicit consent to get your email address(es).

Leaving the “we’ll never trust you again”, “you have ruined your reputation” and “you ruined dotnet OSS for everyone” aside, I think the main issue raised that the SHA256 hash was not enough to protect the privacy of the email address is a valid one. So that is something I’m definitely going to fix. In particular, I’m exploring a very interesting suggestion to use SHA-1 and k-anonimity and a purely offline check that also supports org-wide sponsorships.

NOTE: as a side note for folks claiming how I ruined my reputation. I have

never promoted Moq in any way, not doing any talks, not doing any videos, podcasts, interviews, workshops, training or consulting of any kind on it. I barely wrote a few blog posts back in the day like when I shipped 3.0 in 2009 or when I came up with the super cool (to me at least) Linq to Mocks feature. I mostly didn’t even bring it up in casual conversation with friends and colleages at conferences, MVP summits or whatever.

So, for those who think I’ve been pushing Moq down everyone’s throat just so down the road I can monetize it, I’m sorry to disappoint you. It wasn’t even all that surprising to me that even some of my favorite coworkers didn’t know I was the author of Moq:

hold on, how did I not know that you wrote Moq?? It was you?! Awesome job! I've been using it!

— Kirill Osenkov 🇺🇦 (@KirillOsenkov) July 10, 2017

Transparency

Many felt that my blogging and tweeting and slowly rolling out the feature to my other smaller projects wasn’t enough. That it should have been more obviously visible, discussed in the project repo itself, with sufficient time for feedback from the community and so on, even if I sent a PR to the repo to add the feature 4 days before the first comment from users about it and a subsequent PR to remove it.

I can understand the sentiment, even if I don’t entirely agree with it. Perhaps I’m too impatient, what can I say.

Why are you reinventing the wheel?

It was either:

- OSS is a thanksless job, everyone knows it. Live with it or don’t do it.

- You should just switch to a commercial license.

- Your intention that developers pay from their own pocket is ridiculous and nobody does it that way, it will never work.

I read insightful tweets from many folks I deeply respect, sharing their personal experience with OSS and how they have been able to sustain it (or not). I deeply appreciate all feedback, and I’m not going to try to address each one individually, but I’ll try to summarize my thoughts on the above.

Any one of the above three points are valid and the whole thing might be a waste of my time. But there are some things that are unique this time around, I think:

- GitHub Sponsors is still in its infancy, with many commenting that most companies don’t even know it exists. Its model is also very different from other approaches in that it encourages individual developers to sponsor other individual developers, for a start. As recently as last April, GitHub announced general availability of organization-funded sponsorships, which is a game changer in that regard. When I started working on SponsorLink back in January, this wasn’t even a thing yet.

- The dotnet OSS ecosystem is much more mature than when I made the initial commit more than 15 years ago, with a lot more projects and a lot more users.

- Being a content creator is an actual thing many folks make a living from, with more and more platforms offering this possiblity way beyond YouTube (i.e. X now too!).

OSS as content creation

Many don’t really agree with my view on this, but I think producing OSS is also a form of content creation. I sporadically blog and tweet, but what I really enjoy doing is just creating useful tools and libraries that make my own life easier or are just interesting ideas to explore, and I like doing them as OSS because when I started my C#/.NET journey, log4net was almost the only OSS project around with a significant code base that I could learn from. I want to pay it forward by also sharing what I learn, even if it’s just a small thing.

Most folks probably assume Moq is the only thing I ever did in my 20+ years of doing OSS, but I have a long list of packages which are all OSS. Yeah, all 317 of them as of today 😅. Granted, none of them is remotely as widely known and used as Moq, but that’s probably because they address more niche scenarios, which might nevertheless be useful for folks, even if it’s just to learn some techniques or patterns. For example, I go back to my own ThisAssembly quite often when doing source generators, and I’m pretty sure it was one of the first to come out.

As such, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to consider OSS as a form of content creation, and as such, it’s not unreasonable to consider monetizing it in a different way to traditional software comercialization. I’m honestly not all that excited by the prospect of setting up a company around a single project. As you can tell from my packages, personal and organization repositories, my interests are varied and I like to explore different things.

On Moq

That said, anyone who has created a non-trivial library from scratch can tell you that it’s a significant time investment, unlike a blog post, a tweet or even a YouTube video. I’m not saying it’s more or less valuable, but it’s not something you can just do in a couple of hours over a weekend (unless it’s a sample or a small proof of concept or utility).

Let’s take my attempt to rewrite Moq from scratch as an example. I started

working on it back in 2017 (for the anniversary edition as I fondly named

it back then:

no more run-time proxies in #moq (10th) anniversary edition mean you'll be able to mock anywhere .NET standard 2.0 is supported!

— Daniel Cazzulino 🇦🇷 (@kzu) July 10, 2017

I have since renamed the repo to moq/labs and archived it as recently as last June 30, 2023.

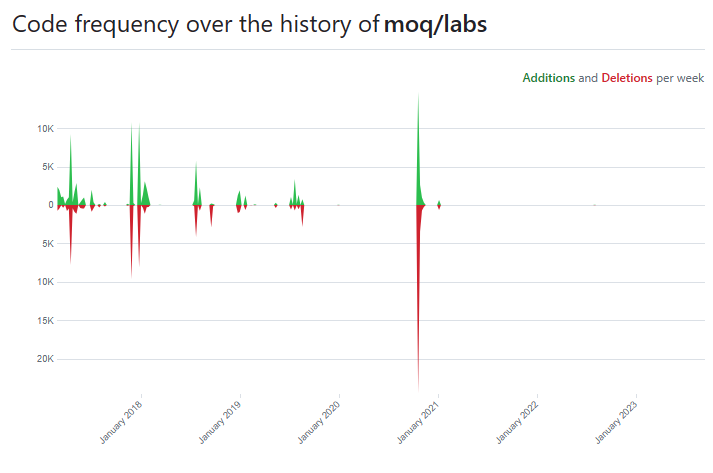

You see, I really really did want to give the community a fresh Moq that took advantage of all the learnings I accumulated over years of doing all sorts of cool .NET tooling, IDE extensibility, code generation and much more. There were many new approaches to explore, with a more clear focus on extensibility and composability of features, so folks didn’t have to send PRs just to add this or that functionality (since Moq itself never had extensibility in mind). You can see how I made many attempts with spikes of intense work over the years:

The large spike at the end of 2020 was when I left Microsoft to pursue other interests, and I was able to dedicate a few months to it. I was really excited and worked intensely on Stunts/Avatar(s), which was the core of the new Moq: a brand new proxy generation engine that leveraged compile-time source code generation instead of run-time emit like Castle Core did.

![]()

I can’t find a working tool like Ohlo (from back in the day, to calculate man-hours) anymore, but I spent months, working mostly full time on it. Even that wasn’t enough. I didn’t want to give up entirely, so by January 2021 I set up a GitHub Sponsors account and thought to myself that if I could get enough sponsors, I could dedicate more time to it. I didn’t really promote it much, but I did get a few sponsors, with Christian Findlay being my first ever sponsor by the months’ end.

Before people get all bent out of shape about Moq... Let's take a few things into consideration.

— Christian Findlay (@CFDevelop) August 9, 2023

Firstly, you probably ain't paying for the libraries you use. Are you even asking your employer to contribute?

Secondly, handing over data is the price you pay for getting free…

NOTE: thanks for that Christian, I really appreciate it.

I added the Sponsor badge to the Moq repo

almost a year and a half ago. That’s around the time my friend

Kirill started sponsoring along with

a few others. But as many have pointed out, there’s really no significant

take rate of GitHub Sponsors in the dotnet OSS community (or any others?).

As the months flew by, and I was unable to dedicate more time to it, I started to consider ways in which I could make it more sustainable. I continued creating and shipping many other OSS projects, but I kept thinking about Moq every now and then. Earlier this year, back in February, I shipped the initial release of SponsorLink, which I had been working on for a few weeks. I started slowly integrating it into my smaller and newer projects, which went over several months with absolutely zero feedback from anyone.

By the end of June I noticed some things were broken in CI for the main Moq repo, and I decided to take a look. That’s when I sort of assumed I was never going to be able to put any serious work on a new Moq, and I decided to rename moq/moq > moq/labs and archive it. and rename moq/moq4 > moq/moq (since there didn’t seem to be a point in keeping it stuck at v4 forever now). I also archived the proxy framework devlooped/avatar

![]()

NOTE: the project wasn’t entirely ignored by absolutely eveyrone, it did have 132 stars after al! But that didn’t generate any significant traction as far as sponsorships or feedback either.

Then at the beginning of this month, I decided to spend some time fixing whatever was broken, and thought to myself: let’s just give this thing one last chance. Fix all the minor issues, add SponsorLink and see what happens. Well, let’s just say it didn’t go entirely the way I expected.

Sure, I could have communicated all this at length in the repo itself, but honestly: the PR was sent 4 days earlier before even the first comment. Even the main project contributor (the awesome Dominique) had been slow to respond to folks for quite a while (his last merged PR being from way back in January).

For all I knew, the project was almost in a zombie state, and I was on the verge of entirely giving up for good on it.

And now after the whole thing blew up, folks are acting like their life depended on the project. As if nobody could just fork it and move on while I tried to rescue the last breath of enthusiasm I had left for it.

On SponsorLink

Now, I understand folks weren’t thrilled by my very very early v1 of SponsorLink. Sure, there are many rough areas and things to fix and improve. Please DO engage, as I’m most certainly not going to just give up on it just yet, and I most definitely disagree with those that think the status quo is just fine and we should just leave it at that.

This is just a statement of fact, take it as you want but believe me it’s my honest feeling at this fork in the road: either SponsorLink works acceptably for folks and it gets significant traction (for myself but also others wishing to get sponsored for their OSS work), or I’m just giving up on OSS entirely.

I would MUCH rather we put together our significant collective brain power to make OSS sponsorships a commonplace occurrence in the dotnet OSS community, than just give up on it entirely.

How about organizations?

My initial intention was/is that SponsorLink should encourage fellow developers that one day might be OSS developers themselves too, to sponsor the projects they use and enjoy. As a matter of personal gratitude and to achieve some level of a personal connection that goes beyond simply reporting issues and complaining when things don’t work great.

One area where I think most OSS devs are in agreement is that doing this seems like not only a thankless job, but an actually hostile one at times. Too many demands, sometimes not even politely asked, and you simply never get to hear from folks that are actually happy using it. This is not exclusive of OSS software, mind you. When I was at both Xamarin and Microsoft (Visual Studio) afterwards, it was easy to feel the same, since your only feedback channel is typically the issue tracker where folks report problems.

If you had a more personal relationship (even if is through the $1 sponsorship), you would keep in mind the individual(s) behind the project because you actively reached out for your pocket. So when it’s time to report an issue, I think you’ll be more likely to remember the person and be kinder.

As an OSS developer, seeing an issue report tagged with a Sponsor label, likewise, will remind you that they care about you, personally, and you are likely going to be more eager to help.

That said, I realize that not everyone chooses the libraries they use, in particular in larger organizations. So I think now that there is growing support for org-wide sponsorships from GitHub Sponsors, it should also be supported.

The way this would work is to consider developers that belong to

the given organization (i.e. they have an email that matches the

org-validated domain) as sponsors too.

How could it scale?

Many have pointed out that if 300 OSS packages used SponsorLink, it would be a nightmare of diagnostic messages in the editor, and that it would be an economic disaster if they had to personally sponsor each one even if it was with $1 each.

This is a fair point, even if I think it’s a bit early to plan for

basically a v3+ of SponsorLink. One way this can be solved is by

sponsoring a (say) Sponsorware organization, which collects a

Spotify-like fee, which is then split based on usage.

Closing thoughts

Imagine if you could have an experience like the following:

- You find an issue with a library you use, which is sponsorable

- You open an issue, and sponsor the repo with a one-time donation mentioning the issue you’d like fixed for the $X amount you’re sponsoring for. (YES, even reading your issue and responding to it takes time and therefore money)

- SponsorLink detects all this automatically and auto-tags the issue as “up for grabs for $X”

- More folks can up-vote the issue with more money via one-time sponsorships just like the first guy.

- At some point, someone is assigned the issue and works on a fix. Once the PR that fixes it is merged, the accumulated money goes automatically as a one-time sponsorship to the contributor.

And now you have an ecosystem where folks can get paid for their work, and you can get your issues fixed faster by sponsoring them.

So don’t tell me the status quo is just fine. It’s not. It’s not fine that a newcomer to the project, looking to learn something but also earn something, has no way to get paid for their work.

Hopefully we can all work together to make this (or some version of it) a reality.

/kzu dev↻d