When we started working for Xamarin as consultants, a couple years ago, it was nothing short of amazing for us that Xamarin had already achieved a pretty solid “F5 experience” with an app building on the Mac and debugging like any regular local .NET app. I had the same feeling the first time I did the same thing against an Azure website. Felt like magic (in the Arthur C. Clark way).

During the past year and a half since the we joined Xamarin, we iterated (among other things) on this key component of the developer experience, culminating in our most recent release, Xamarin 4. What started as a (more or less) batch process of “zip sources, HTTP post to Mac, build, run” (with frequent rebuilds needed), is now a fine-tuned granular incremental build system driven by MSBuild, connecting to the Mac over a resilient, auto-deployed and always-on messaging layer running on top of a bi-directional binary protocol over TCP, secured by an SSH tunnel.

At the user experience level, it might seem that little has changed other than a fancy new connection dialog. But as Tim Cook said “the only thing that changed is everything”, so I’ll go over the details of how it works today with the new Xamarin 4 experience.

MSBuild and Incremental Builds

For anything but trivial apps, achieving incremental builds is key for productivity: you don’t want to be copying unnecessary files over the network to the Mac, neither you want to be optimizing PNGs, compiling storyboards and what-not if none of the source files have changed.

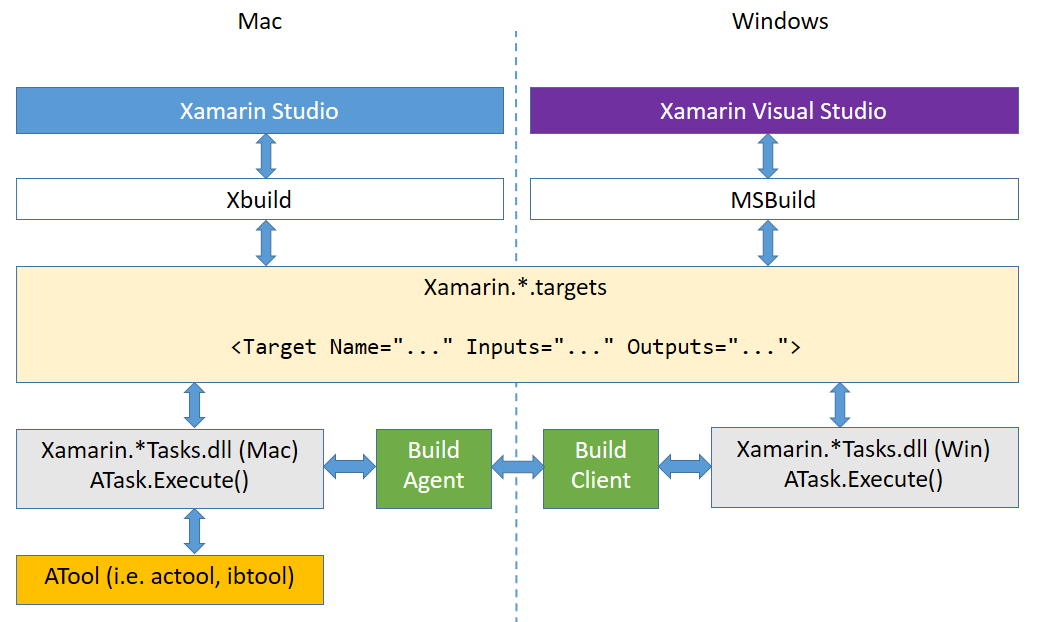

MSBuild (and XBuild on the Mac) already support incremental builds, so the first challenge was to move away from batch-style of invoking XBuild remotely, to a fully “MSBuild-native” solution. Also, we wanted to share 100% of the build logic from Xamarin.iOS targets on the Mac. So the way it works today is:

You can see that exactly the same targets and tasks are shared between the Mac and Windows. This allows us to minimize inconsistencies between VS and XS builds. The only difference is that the Windows version of the tasks do a remote invocation to the Mac whenever the tasks that need to run on the Mac are executed. We evaluate tasks individually to determine if they must run remotely or if they can be run locally.

The unit of remote invocation to the Mac is the MSBuild

Task.Execute

One example of a task that always runs remotely is compiling iOS storyboards, since the tools to do so are provided by Xcode. An example that doesn’t is the C# compiler itself, since the source code can be compiled to IL by Microsoft’s compiler on Windows without requiring a roundtrip to the Mac.

Some parts of the build are done on Windows, some parts on the Mac

The next step was to improve the targets to provide relevant Inputs/Outputs to enable incremental build. An interesting challenge there was that for MSBuild to determine that a given target doesn’t need run again (or that certain outputs are out of date with regards to their inputs), the Outputs files need to exist on the Windows side. But since all we need those output files for is for incremental build support, they are actually written as empty files on Windows :). MSBuild doesn’t care, as long as the timestamp on those files can be compared with the Inputs to detect the out-of-date items.

This mechanism existed prior to Xamarin 4, and we just replaced the underlying remote call protocol, which was almost trivial to do since the core changes to unify XS/VS builds had already been done. Our goal was to have at least comparable performance to our previous releases.

Now that the underlying communication infrastructure has shipped, we’ll focus on fine tuning the targets and tasks to leverage incremental build support even more. Our goal is to achieve substantial performance gains moving forward, and we could certainly use your feedback, especially if you find some cases where builds are considerably slower than local builds on the Mac with Xamarin Studio.

Remote Communication

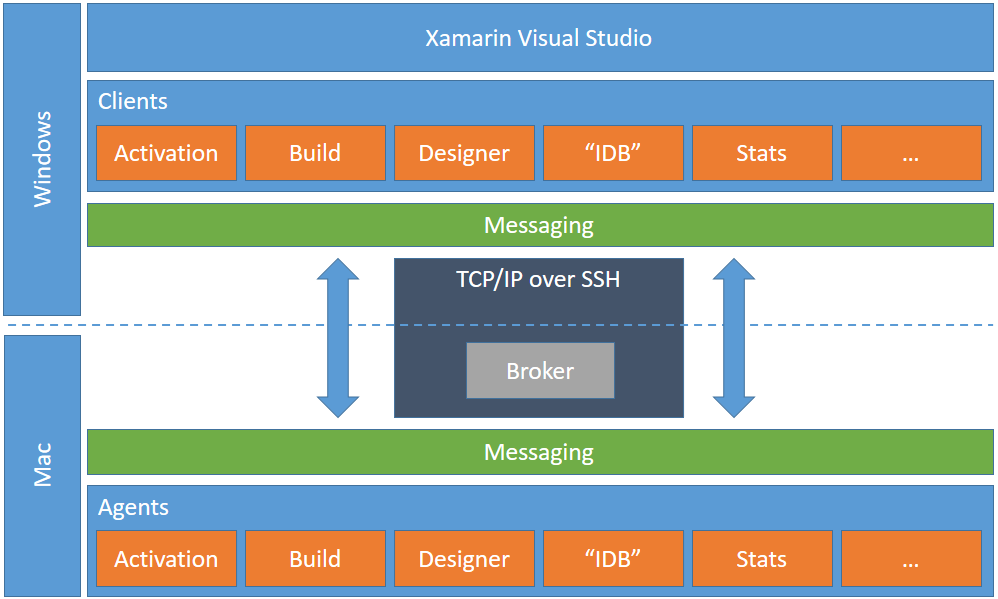

The underlying communication facilities that Xamarin provides within Visual Studio are consumed by fairly independent components (we call them Agents):

- Activation: ensures that the Mac is properly activated

- Build: performs the remote build task invocation

- Designer: provides the rendering for the iOS designer

- IDB: provides similar functionality to ADB (Android Debug Bridge), hence the name, an acronym of iOS Debug Bridge (we don’t like the name so much nowadays ;)). Basically exposes list of simulators and devices available on the Mac

- Stats: we support collecting some stats (execution time, payload sizes, etc.) for diagnostics.

From top to bottom, the flow is:

- When Xamarin starts within Visual Studio, it automatically establishes an SSH connection with the Mac, deploys the Broker (if necessary), starts it and then starts all the Agents (which you see in real-time in the status bar or the spinner icon tooltip on the connection dialog)

- Agents use the exposed API (IMessagingClient) to send/post/reply messages (remember it’s bidirectional!)

- The Messaging layer communicates over TCP/IP within the SSH tunel with the Broker, which forwards the message to the Mac-side agent that registered to receive the message.

- The process is the exact opposite if the Mac side agents need to communicate with the VS ones, which are in turn registered to receive certain messages.

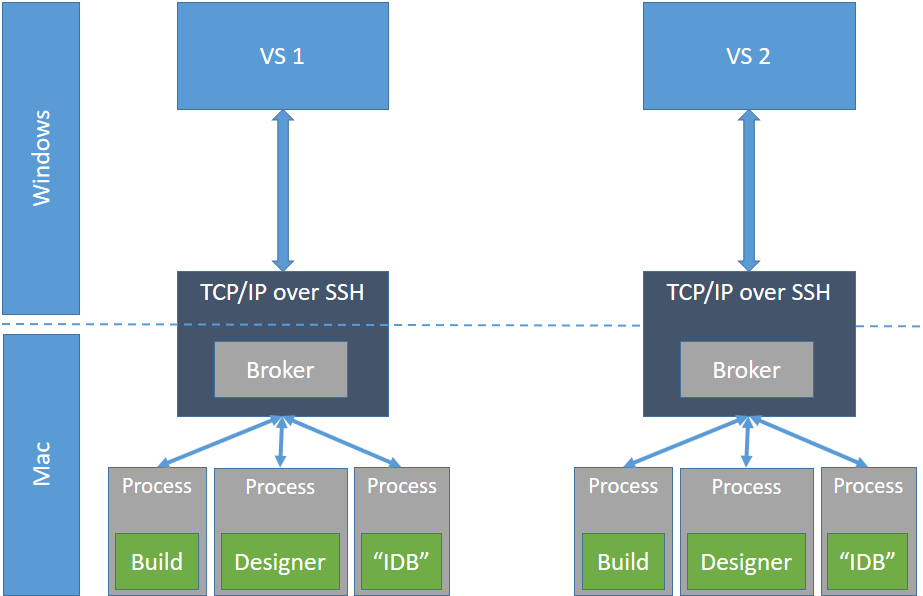

In previous versions of Xamarin, an unexpected error on any of the individual components on the Mac could cause the whole build host to stop working, requiring manual intervention by restarting it. In Xamarin 4, we implemented process-level isolation for unrelated components:

One key change from our previous versions is that now Visual Studio drives the Mac side too. Since it connects remotely to the Mac via SSH as a local interactive user account, it can start processes, copy files, fetch logs, etc.

Visual Studio controls deployment, versioning and manages processes on the Mac

As shown in the previous image, there is another isolation boundary at the Visual Studio process level. This ensures that multiple instances of VS can simultaneously connect to the Mac seamlessly. The broker and individual agents can all be recycled independently too. The ports used by the broker and agents are negotiated automatically to avoid collisions too.

And as soon as Visual Studio disconnects from a Mac, all processes are stopped.

In a future post, I’ll go into more detail on the protocol underlying the Messaging layer. If you’re curious, it’s MQTT :)

/kzu dev↻d