API exploration, whether third party or your own, is a necessary and unavoidable part of regular development. There are many mechanisms available today for doing such exploration in a one-time, throw-away style, but it might be worth considering keeping those explorations around in your code base and even make them easily executable within the IDE afterwards, for further learning or other team members’ benefit.

Typical ways you can tackled this are:

-

File | New | Console Application: some have even gone so far as to suggest a good indicator of a candidate’s willingness to explore new things is to look at the list of his recent solutions in the starting VS dialog. If you see ConsoleApplication142, it’s likely this person regularly tests new things :). I’ve done this countless times in the past, but it’s no longer my favorite way. The obvious benefit of this approach is its simplicity and having the full power of VS and its debugger for the exploration. The obvious drawback is it’s nearly impossible to find that experiment you did some time ago and now you need to go back and revisit.

-

LinqPad: my next favorite after way too many console applications, was (and sometimes still is) LinqPad. It’s a great tool with many improvements over a console app (like “dumping” an object in a nice formatted way), which makes it easier to keep around those experiments since they can be saved to a self-contained file that keeps not only the source but also whatever nuget packages you need for it. It’s lightweight, fast, has a built-in debugger and so on. I’d say it fits a nice niche between VS Code and Visual Studio.

-

C# Interactive: I’ve found this convenient mostly for one-liners, creating GUIDs and the like, but I don’t use it regularly and keep forgetting it’s built-in VS, switching to LinqPad in many cases where I could just use this feature. There is, however, a somewhat worrying infobar that displays in VS telling me the C# Interactive tool window is slowing down VS startup, which causes me to close it and entirely forget about the feature subsequently :(.

-

SmallSharp: this offers a combination 1. and 2. above. It’s a simple nuget package you install in a console application which allows you to have many top-level programs you can quickly select and run right from the Run button. I keep a GitHub repo with a single console app with this, which at the time of this writing has 20+ top-level C# files with various experiments. The obvious benefit of this approach is being able to keep everything in a single place and having full IDE support. Obvious drawback is that for a just a few lines of code, it seems overkill to have an entire file.

-

Ad-hoc tests: the awesome TestDriven.NET by Jamie Cansdale is an amazing feature that allows you to run any arbitrary method in any project (NS2.0 or “test project” with other unit tests in it), without having to annotate it with anything. The benefit of this approach is that you can keep these ad-hoc test methods alongside your “real” unit tests, but they would just never run automatically. They are also useful for doing custom cleanup of your environment, or any other semi-recurring things you might need, but which you run exclusively manually.

-

IDE-only unit tests: ad-hoc tests are great, but may not be supported in all versions of Visual Studio (at the moment, Visual Studio 2022 is not supported, for example), and requiring an entire team to use a given tool that happens to be your favorite, isn’t great either. If the methods showcase some API usage, or are actually samples of how to use APIs provided by the same solution itself (but are not intended to be run as acceptance or integration tests, which might slow down CI unnecessarily), it would be invaluable to be able to run then in the IDE without depending on any additional tooling. For this purpose, it’s fairly easy to extend xunit to only allow execution of the tests when running them from inside Visual Studio, and not CI or the CLI, as shown in the next section.

IDE-only Unit Tests

The “trick” is to simply extend both FactAttribute and TheoryAttribute to check

for the right environment variables and skip the test by default otherwise:

public class IdeFactAttribute : FactAttribute

{

public IdeFactAttribute()

{

var isCi = !string.IsNullOrEmpty(System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("CI"));

var isIde = !string.IsNullOrEmpty(System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("VSAPPIDNAME"));

var shouldSkip = isCi || !isIde;

if (shouldSkip)

Skip = "This test only runs on the local development environment, inside Visual Studio.";

}

}

public class IdeTheoryAttribute : TheoryAttribute

{

public IdeTheoryAttribute()

{

var isCi = !string.IsNullOrEmpty(System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("CI"));

var isIde = !string.IsNullOrEmpty(System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("VSAPPIDNAME"));

var shouldSkip = isCi || !isIde;

if (shouldSkip)

Skip = "This test only runs on the local development environment, inside Visual Studio.";

}

}

NOTE: you could even name them

Sample*instead ofIde*, if that’s the purpose they serve, just to make that clearer when browsing the code.

When you apply the [IdeFact] or [IdeTheory] attributes, tests are discovered

by the built-in VS runner as well as the command line one, but they will be skipped

unless runnning inside Visual Studio. The environment variable VSAPPIDNAME is set

by devenv.exe and is propagated to the child test discoverer and runner from within

VS. I’ve also added a check for CI

so they never run in a build server, just in case.

Given the following code:

public class SampleTests

{

[Fact]

public void RegularUnitTest()

{

Assert.True(true);

}

[Theory]

[InlineData("foo")]

[InlineData("bar")]

public void RegularTheory(string value)

{

Assert.NotNull(value);

}

[IdeFact]

public void IdeOnlyUnitTest()

{

Assert.True(true);

}

[IdeTheory]

[InlineData("foo")]

[InlineData("bar")]

public void IdeOnlyTheory(string value)

{

Assert.NotNull(value);

}

}

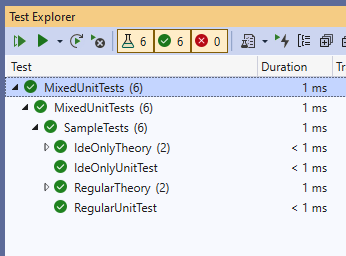

You can run them all from VS:

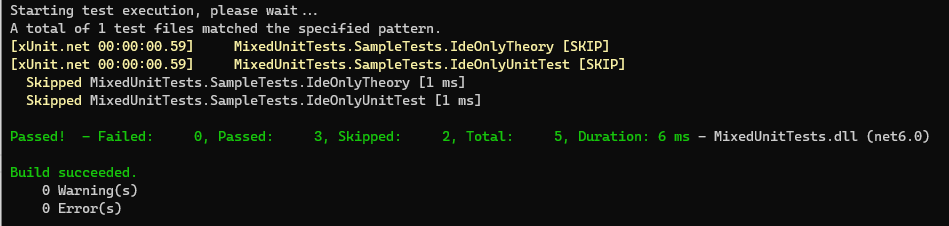

But from dotnet test, you’d see:

So nowadays, I use a mix of SmallSharp and IDE-only unit tests. And as soon as TestDriven supports 64-bit VS2022 I’ll likely add a mix of ad-hoc too.

/kzu dev↻d